In his office, Brian Kischnick pulls out two rolled-up maps of downtown Royal Oak and downtown Birmingham and places them individually over an aerial photo of the 127-acre Troy civic campus. They both fit, with room to spare.

Those are the stakes that Kischnick, Troy’s city manager, and a team of planners have in the back of their minds as they shop around a master plan for the campus that would cost at least $350 million and bring at least 850 residences and hundreds of thousands of square feet of walkable retail space to the city, one of Oakland County’s economic engines — even with no downtown.

Troy is one of several suburban communities thinking like developers, looking at increasingly valuable municipal real estate holdings and viewing them as opportunities to create bustling, walkable urban areas attractive to both millennials and baby boomers, and bring in more city revenue in the process.

Royal Oak, Northville, Warren and Commerce Township, just to name a few, are all taking aim at the new lust for downtown living.

For more than six months, Troy has been working with Bingham Farms-based Core Partners LLC and Birmingham-based Gibbs Planning Group Inc. to develop a master plan for 127 acres of city-owned land on which Troy’s civic complex sits nestled between I-75 to the west, Livernois to the east and north of Big Beaver Road.

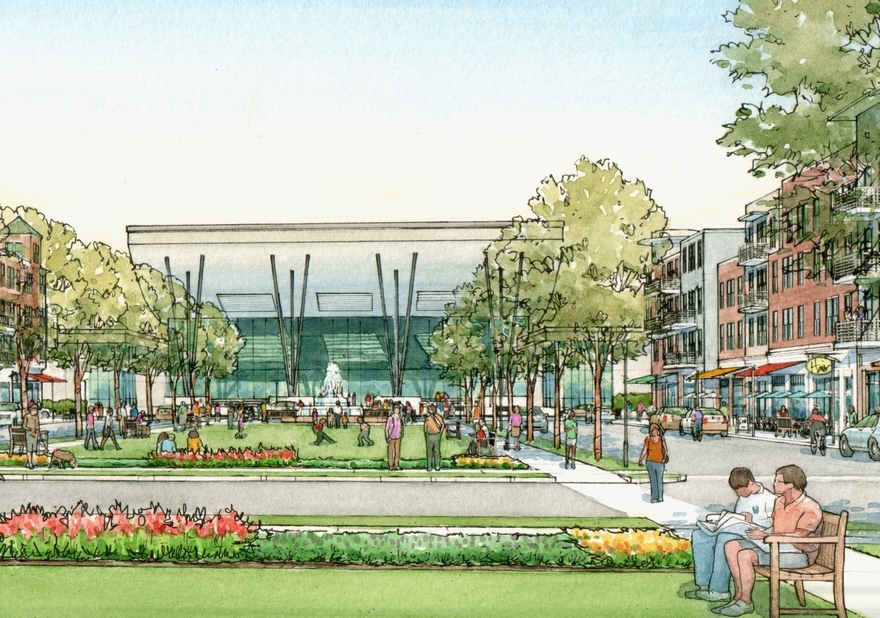

Not only does the site contain City Hall, but also the police department, library, community center, an aquatic center and the 52-4 District Court. Those buildings would remain largely unchanged, minus a new facade and clocktower for City Hall.

It’s the acreage surrounding those buildings that’s expected to see the most activity as retail spaces, townhouses, live-work units, condominiums, apartments and cottage homes are built, plus a 300-room hotel.

The planners and city council and planning commission have come to a consensus on a master plan for the area that involves the development of what Robert Gibbs, the urban planner and landscape architect on the project, likened to Troy’s version of downtown Birmingham, fresh out of the City Beautiful planning movement of the 1920s that built downtowns around civic buildings.

“The overall goal is to give Troy a downtown that they never had,” he said last week.

The site, said Matt Farrell, founder of Core Partners, is a gem that has been overlooked by developers.

“It has been right underneath everybody’s noses for a long time,” he said.

Ambitious plan

Troy, one of Oakland County’s economic hubs with 83,000 residents and 13.26 million square feet of office space, is almost 34 square miles of large office buildings, high-end shopping centers like the Somerset Collection, department stores, strip malls, restaurants, houses and apartment buildings. It has 125,000 workers during the day.

The problem, according to Gibbs?

“They have to get in their car and drive to Chili’s for lunch,” he said.

If its residents and workers want a walkable community, they have to look to other areas like Birmingham, Royal Oak, Rochester or Ferndale, which have vibrant downtowns nearby with their own unique personalities and challenges. Birmingham and Ferndale have parking shortages. Royal Oak has a dearth of office workers. Rochester is a trickier commute.

The Troy project could be less daunting with what essentially is a development blank slate and a massive block of land with substantial infrastructure already in place, not to mention the residential and employment base to support it.

What happens with Troy’s property remains an open-ended question. Things could change; five-year projections for the site based on market studies, said Dave Mangum, planning associate at Gibbs Planning, are enormous: 2,000 or more residences, 600,000 square feet or more of retail space.

Yet the planners are being conservative with their early project estimates: 850 residences, 180,000 square feet of retail at a $350 million price tag.

Troy’s plan, presented last week to what Kischnick said were 50 to 100 developers at the International Council of Shopping Centers deal-making conference in New York City, could take years to materialize. First, a master developer has to be chosen; a request for qualifications could be sent out next year.

Best-case scenario: “Some (construction) activity” beginning in 2018, said Larry Goss, executive vice president of Core Partners.

Happening elsewhere

It’s not just Troy that is taking its real estate and putting it in the hands of private developers to turn into something urban and unique.

The largest in the works is the Commerce Towne Place project in Commerce Township, which is well over 300 acres of land.

For more than a decade, Commerce has plugged away on the project at M-5 and Pontiac Trail, with a massive 340 acres (130 or so would be preserved as parkland). The project, chugging along after coming to a screeching halt in 2008 with the economic collapse, is expected to bring about 700 single-family houses, senior housing units and townhouses to the market, along with 550,000 square feet of retail and office space in a project expected to cost more than $270 million.

The land for the project is owned by the township’s DDA, which purchased a pair of golf courses and several other large parcels with the Commerce Towne Place vision in mind.

In Royal Oak, the plans for a new $100 million city hall in the Royal Oak City Center development have been delayed slightly but are still proceeding as the city commission mulls whether to lease 30,000 square feet for city operations in a multitenant office building to be built or be the lone user in another one, said Ron Boji, president and founder of Lansing-based The Boji Group, one of the developers.

“Certain communities have had — and mostly everyone has had — very, very modest growth because of the downturn in the economy in Michigan the last 10-12 years,” Boji said.

“They are using their own infrastructure, whether that be courts, police, a city hall, other civic items such as conference centers, things of that nature, as stimulators to a private-public partnership to bring on other items such as retail, residential and office.”

Boji’s development group also includes The Surnow Co. and RAD Development Group, both based in Birmingham.

The 190,000-square-foot building was originally planned to include 30,000 square feet for city government operations and about 130,000 square feet of leasable office space with 20,000-square-foot floor plates. Financing for the project is now expected to close in the spring or summer.

The building would also include a rooftop garden terrace and event center, along with leasable space for a specialty grocery store and a restaurant with a liquor license, Boji said.

Also included in the project plans are a 533-space, six-story parking deck, a park with an amphitheater and playground, and new Royal Oak Police Department headquarters.

In Northville Township, a former state corrections facility site is planned to be redeveloped into more than 350 residences with 28,000 square feet of retail, three or four restaurants and a 50,000-square-foot anchor retailer, said Dale Watchowski, president, COO and CEO of Southfield-based Redico LLC, one of the developers on the project.

He said the redevelopment of the 57-acre former Robert Scott Correctional Facility site, which was owned by the township, at Five Mile and Beck roads, is expected to break ground in the spring. Some of the residences — which include 111 single-family houses, 66 townhouses and 180 apartments — are expected to be complete late fall next year.

Farmington Hills-based Pinnacle Homes is a developer on the residential components of the project.

In Warren, 210 loft units south and east of city hall at a $32 million development cost have been planned, said Mayor Jim Fouts.

A groundbreaking for the Bingham Farms-based Burton-Katzman LLC project is expected next year.

In Dearborn, the city sold its old City Hall on Michigan Avenue in the east downtown area to a Minneapolis-based developer that converted the three-building campus into 53 lofts.

The ensuing development, the City Hall Artspace Lofts, welcomed its first residents to the $16.5 million redevelopment of the 1920s buildings Jan. 1.

Millennial movement?

Robin Boyle was skeptical at first when briefed on the plans in Troy.

“Incredibly hard to walk around there,” said Boyle, a professor and chairman of the Wayne State University Department of Urban Studies & Planning and a member of the Birmingham Planning Board.

He also said a lot of prerecession mixed-use suburban developments touting walkability were largely paying lip service to the concept.

But he is beginning to change his mind.

“Now, I am beginning to think that the developers are genuinely interested in this and they think the millennial buyer wants to have a tightened development,” he said. “They want to have a chance … to take the kids for an ice cream or buy the paper or get a drink or get dinner and walk there.”

And that’s what Troy hopes to provide, in perhaps one of the least-expected cities in the region.

“Of all places,” Boyle said.

By KIRK PINHO, Crain’s Detroit Business